1. Alias

All types that containing a pointer to data in the heap (or the stack) are aliasable types. An aliasable type cannot be implicitly copied, nor can it be implicitly referenced, for performance and security reasons respectively. There are mainly three aliasable types, arrays (or slices, there is no difference in Ymir), pointers, and objects. Structures and tuples containing aliasable types are also aliasable.

The keyword alias is used to inform the compiler that the used

understand that the data borrowed by a variable (or a value) will

borrowed by another values.

import std::io

def main () {

let mut x : [mut i32] = [1, 2, 3];

let mut y : [mut i32] = alias x; // allow y to borrow the value of x

// ^^^^^

// Try to remove the alias

println (y);

}

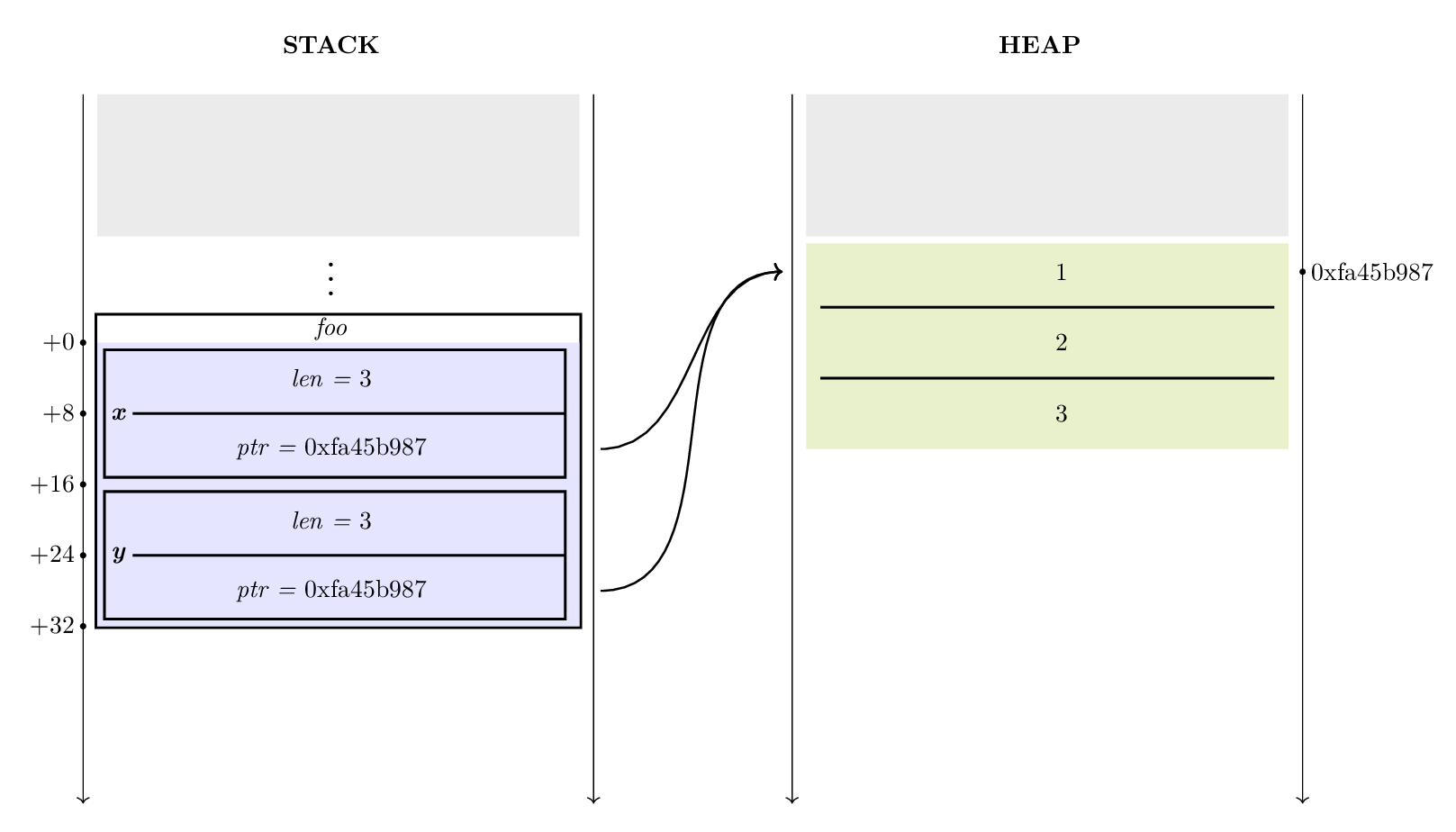

This source code can be represented in memory by the following figure.

The alias keyword is only mandatory when the variable that will borrow the data is mutable and may impact the value. It is obvious that one cannot borrow immutable data from a variable that is mutable. For example, the compiler must return an error on the following code.

import std::io

def main () {

let x = [1, 2, 3];

let mut y : [mut i32] = alias x; // try to borrow immutable data in deeply mutable variable y

// ^^^^^

// Try to remove the alias

println (y);

}

Errors:

Error : discard the constant qualifier is prohibited, left operand mutability level is 2 but must be at most 1

--> main.yr:(5,13)

5 ┃ let mut y : [mut i32] = alias x; // try to borrow immutable data in deeply mutable variable y

╋ ^

┃ Note :

┃ --> main.yr:(5,29)

┃ 5 ┃ let mut y : [mut i32] = alias x; // try to borrow immutable data in deeply mutable variable y

┃ ╋ ^^^^^

┗━━━━━┻━

Error : undefined symbol y

--> main.yr:(8,14)

8 ┃ println (y);

╋ ^

ymir1: fatal error:

compilation terminated.

However, if the variable that will borrow the data is not mutable,

there is no need to add the keyword alias, and the compiler will

create an implicit alias, which will have no consequences.

import std::io

def main () {

let x = [1, 2, 3];

let y = x; // implicit alias is allowed, 'y' is immutable

println (y);

}

In the last example, y can be mutable, as long as its internal

values are immutable, i.e. its type is mut [i32], you can change the

value of y, but not the values it borrows. There is no problem,

the values of x will not be changed, no matter what is done with

y.

import std::io

def main () {

let x = [1, 2, 3];

let mut y = x;

// y [0] = 9;

// Try to add the above line

y = [7, 8, 9];

println (y);

}

You may have noticed that even though the literal is actually the

element that creates the data, we do not consider it to be the owner

of the data, so the keyword alias is implied when it is literal. We

consider the data to have an owner only once it has been assigned to a

variable.

There are other kinds of alias that are implicitly allowed, such

as code blocks or function calls. Those are implicit because

the alias is already made within the value of these elements.

import std::io

def foo () -> dmut [i32] {

let dmut x = [1, 2, 3];

alias x // alias is done here and mandatory

}

def main ()

throws &AssertError

{

let x = foo (); // no need to alias, it must have been done in the function

assert (x == [1, 2, 3]);

}

1.1. Alias a function parameter

As you have noticed, the keyword alias, unlike the keyword ref,

does not characterize a variable. The type of a variable will indicate

whether the type should be passed by alias or not, so there is no

change in the definition of the function. When the type of a parameter

is an aliasable type, this parameter can be mutable without being a

reference.

import std::io

// The function foo will be allowed to modify the internal values of y

def foo (mut y : [mut i32])

throws &OutOfArray

{

y [0] = y [1];

y = [8, 3, 4]; // has no impact on the x of main,

// y is a reference to the data borrowed not to the variable x itself

}

def main ()

throws &OutOfArray, &AssertError

{

let dmut x = [1, 2, 3];

foo (alias x);

// ^^^^^

// Try to remove the alias

assert (x == [2, 2, 3]);

}

As with the variable, if the function parameter cannot affect the values that are borrowed, the alias keyword is not required.

import std::io

def foo (x : [i32]) {

println (x); // just reads the borrowed data, but doesn't modify them

}

def main () {

let dmut x = [1, 2, 3];

foo (x); // no need to alias

}

1.1.1. Alias in uniform call syntax

We have seen in the function chapter, the uniform call syntax. This

syntax is used to call a function using the dot operator ., by

putting the first parameter of the function on the left of the

operation. When the first parameter is of an aliasable type, the first

argument must be aliased explicitely, leading to a strange and verbose

syntax.

let dmut a = [1, 2, 3];

(alias a).foo (12); // same a foo (alias a, 12);

To avoid verbosity, we added the operator :., to use the

uniform call syntax with an aliasable first parameter.

let dmut a = [1, 2, 3];

a:.foo (12); // same as foo (alias a, 12);

This operator is very usefull when dealing with classes, where the uniform call syntax is mandatory, as we will see in chapter Class.

1.2. Special case of struct and tuple

In the chapter Structure you will learn how to create a structure containing several fields of different types. You have already learned how to make tuples. These types are sometimes aliasable, depending on the internal type they contain. If a tuple, or a structure, has a field whose type is aliasable, then the tuple or structure is also aliasable.

The table below presents some examples of aliasable tuples :

| Type | Aliasable | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| (i32, i32) | false | i32 is not aliasable |

| ([i32],) | true | [i32] is a slice, and hence aliasable |

| ([i32], f64) | true | [i32] is a slice, and hence aliasable |

| (([i32], i32), f64) | true | [i32] is a slice, and hence aliasable |

In the introduction of this chapter we presented the notion of Mutability level. One can note that mutability level is not suitable for tuple, as aliasable tuple are trees of type and not simply a list. However, this does not change much, the compiler just check the mutability level of the inner types of the tuple, recursively.